Pilgrimage to my hero father

-

•Reggie Meyer was last seen fighting over the Aegean Sea in 1944

-

•Many questions were still unanswered when his mother died in 2004

-

•But in 2009, Christopher found out his father was buried in a Greek church

-

•Information led him on a journey to the island of Ikaria so he could find peace

By Christopher Meyer, Former British Ambassador To Washington

PUBLISHED: 22:05, 16 November 2013 | UPDATED: 22:05, 16 November 2013

A week after my birth, my mother Eve received a letter from the Air Ministry at 77 Oxford Street in London confirming that her husband, Reggie Meyer, was missing in action.

Air Force Headquarters, Middle East, had reported his setting out over the Aegean Sea on February 9, 1944, and that he ‘was last seen being attacked by enemy aircraft approximately five to ten miles north-north-east of Patmos, one of the Dodecanese Islands’. The letter added that this did not necessarily mean he had been killed.

Such hope as my mother might have had was dashed by a further telegram from the Air Ministry, written in pencil on May 23, which said that Reggie ‘was believed to have lost his life’. I was three months old.

Courageous: Christopher's flight lieutenant father Reggie, centre, with two RAF colleagues

All my life people have asked me what it’s like not to have known my father. To which the only honest answer is, I haven’t a clue. You cannot feel an absence when you have never known a presence.

But there are a thousand things I wish I had asked my mother before she died in 2004. Most of them concern my father. She told me so little of what had happened.

I knew that he had been killed on a mission against German shipping in the eastern Mediterranean. He had been 23. At that age I was a callow youth, starting my career as a diplomat and back in school to learn Russian.

My father was already an experienced pilot, in command of a flight of four aircraft, locked in a life-and-death struggle with the Axis powers.

For many years, I felt an inexplicable hesitation to find out more about the circumstances of his death.

But in April 2009, I received a letter that would lead me on a pilgrimage to a windswept hilltop church on the Greek island of Ikaria where, unknown to the German occupying forces, my father had been secretly buried – enabling me to complete a missing chapter in my life.

After my mother’s death I found a small trove of personal papers, including her wartime diary. She had fled a suffocating neo-Victorian household in Westcliff-on-Sea in Essex by ‘joining up’ in 1939, just before war broke out. Highly intelligent, tall and good looking, she became a cyphers officer in the Women’s Auxiliary Air Force. She began her diary more or less as she left home.

It revealed how she had met Reginald Henry Rome Meyer, and how they married and lived in bliss for a few months in 1943. The chances of Reggie’s survival were slim. He had entered a theatre of war – the Aegean – where the casualty rate for Beaufighter squadrons such as his was 50 per cent.

The shadow of future bereavement must have hung over their wedding. But he was a natural optimist and I have inherited my optimism from him.

He exudes, from the few photos I have of him, a playful cheeriness. He was a solid rugger player, christened Porky by his friends (so that when my mother became pregnant with me, he immediately called me the Piglet). But his few surviving letters to my mother are well written, capable of expressing in a direct and unadorned way his love and how much he missed her. This was a sensitive man.

Her diary is not clear about how they first met. Suddenly, on November 28, 1942, Porky appears for the first time. He starts to pop up with increasing frequency. An entry for February 11, 1943, announces that, to my mother’s delight, Porky has proposed marriage. On March 13, 1943, they are married in the Officers’ Mess at RAF Catfoss in Yorkshire.

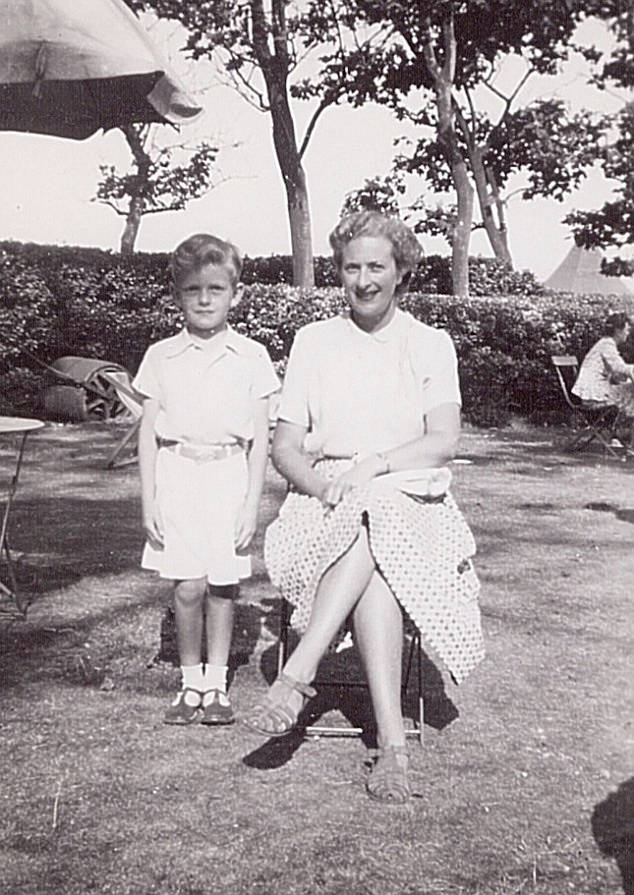

Alone: A young Christopher, left, with his widowed mother Eve in Cornwall

Quite a few photographs have survived. Nearly everyone has a cigarette in their hand. The bride is ecstatic, the groom genial in his contentment.

After Reggie and my mother have said goodbye for the very last time on November 4, 1943, she lapses into inconsolable despair. The diary entries stop, never to resume.

Reggie’s Piglet would surely have turned out very differently had his father survived the war.

As a child, I was nervous. There was endless warfare between my mother and grandmother, the former trying to create an independent career for herself, the latter bitter and possessive, prying endlessly into her daughter’s life. It did not help that both were recently widowed and we were all living in the same house. I became a pawn in the conflict between mother and daughter.

My mother decided to resume her promising career in the Women’s Royal Air Force, which took her first to the Air Ministry in London and then to an RAF station in East Anglia.

She confided a good deal in our local GP, Dr Townsend. She was worried about how skinny I was and my lack of appetite. But my mother’s bigger worry was leaving me to be brought up by my grandmother, and being replaced by her in my affections. Dr Townsend recommended sending me to boarding school.

And so, in September 1951, at the tender age of seven, I found myself a boarder at Sutton Place preparatory school in Seaford, East Sussex. From then on, for the next 25 years until I married, I spent most of my time away from what I called home.

For three years, I suffered a despairing homesickness that would ravage me for the first three weeks of each term. Every night I would cry myself to sleep.

Lost: Christopher's father was last seen being attacked by enemy aircraft 10 miles north-north-east of Patmos, one of the Dodecanese Islands in the Aegean Sea

Suddenly, at the start of my fourth year, the homesickness stopped. By then my mother had remarried and I had moved in with her and my new stepfather. They lived in a large Victorian house in the village of Duxford outside Cambridge, where my stepfather commanded the RAF station.

I loved being there. There was a gigantic garden with all kinds of secret places, and I would play there endlessly, climbing trees and letting my imagination run riot.

But suddenly, I was obliged to admit to the most intimate family rituals an almost complete stranger, my stepfather. Kissing a bristly face before I went to bed felt very odd. I always felt awkward in his presence; I never felt able to call him ‘Uncle Mac’, with which, for my benefit, my mother had decided to christen him.

To the day he died, there was no real engagement between us. We never warmed to each other.

I never forgave my mother for sending me away to boarding school. I realise now that to a large degree she lived through me, her ‘golden boy’, as she once called me, the sole fruit of her relationship with my father. My relations with her were terribly conflicted.

For decades, my mother’s file of documents about my father’s death lay undisturbed in a drawer of her desk. I had a few photographs of my father, but that was it.

Memories: Reggie, who was called 'Porky' by his friends, married Christopher's mother at RAF Catfoss in Yorkshire (pictured) which was used as an airbase during WWII

When she died, I inherited the file along with her wartime diary and her sparse correspondence with my father. I poked around in my mother’s diary and briefly looked at the Ikaria papers.

I also made regular pilgrimages to my father’s grave at the Commonwealth War Cemetery in Phaleron, an Athens suburb, where he was reburied in the 1950s after being disinterred from Ikaria.

'All my life people have asked me what it's like to have known my father. To which the only answer is, I haven't a clue'

But I was not yet ready to do more than that until 2009, when I received a letter from Dr Ian Donnan, a medical examiner to the Civil Aviation Authority.

He was writing on behalf of ‘a friend who, although born in the UK, is of Greek ancestry and now lives permanently on the island of Ikaria’. His friend had heard from locals the story of the shooting-down of my father’s Beaufighter and how he and Peter Grieve, his navigator, had been buried on the island. If I did not find it too intrusive or painful, they were keen to know more –assuming I was the son of Flight Lieutenant R.H.R. Meyer.

I summarised for Dr Donnan what I knew from the family papers. He put me in touch with his friend in Ikaria, a lady called Anastasia Douris, known as Topsy. She had retired to Ikaria, and had become a significant expert on Ikarian history and culture.

Her diligent research spurred me at last to do likewise. It was almost a competitive thing. How could I have a complete stranger know more about my father’s death than I?

In the summer of 2010, Topsy and I met for lunch at the Ivy in London. We hit it off and made a provisional plan for my wife Catherine and me to visit Ikaria the following year. She would introduce us to the witnesses of the Beaufighter’s shooting down.

We travelled to Ikaria, a wild, untamed island named after Icarus and situated 30 miles off the Turkish coast, in the first week of September 2011.

As is the way with witnesses, each told a variation on the same theme. Nicholas Batuyios, 17 years old at the time, had run from the village of nearby Cambos when he heard the crashing aircraft. He found it in flames, with two local men fighting for possession of the rubber landing wheels. Soon a small crowd of 50 to a hundred people had arrived, many of whom were taking pieces of the aircraft even as it burned.

After a few days, said Nicholas, only the engines had remained. The metal had been turned into pots and pans, knives and forks. The rubber had been used for shoes, such was the islanders’ impoverishment.

Marika Pateraki, now a beautiful 92-year-old, had dressed the bodies with flowers. Then she and two other women had sung a well-known song – ‘You have chosen to die, when in spring everything is growing’.

Afterwards, they had carried the bodies to the church of St Elias. Father Krokos had presided. The teacher at the local primary school, Andreas Stavrinadis, had given the address. Despite the bad weather and fear of the Germans, a large crowd had come. As the bodies were buried, the crowd sang the Greek national anthem.

Journey: Christopher made regular pilgrimages to his father's grave in the Commonwealth War Cemetary in Phaleron, Athens

We visited the site where the Beaufighter had crashed. There was no physical sign of any kind. I was content to view it from a few hundred yards – a nondescript piece of scrubby hillside in the Mesaria ravine between the villages of Akamatra, Daphne and Frandato.

One witness, who as a child had been grazing goats dangerously near the crash, said Reggie had tried to bring the Beau down on a small, flatter piece of land next to the ravine. But the aircraft had bounced off, cartwheeled in the air, and crashed in flames on the hillside.

Much of the time, as people described the death of a father I had never known, it was as if Reggie were a remote historical figure.

It was only when, after a steep climb, Catherine and I reached the windy hilltop with its tiny church that I found emotion coursing through me. It was just too unbearably sad – youth and a marriage brutally curtailed not a mile away in this rugged, inspiring landscape.

I longed to believe that Reggie was looking down as his only son accorded him the honour that was his due. We were joined on the hillside by a small group. There were two priests, Fathers Nico and Aleko. The charismatic Nico conducted the ceremony, saying prayers for Reggie and Peter and blessing the ground where they had been buried. Then the Mayor, Christophoros Stavrinathis, presented me with a certificate conferring honorary citizenship of Ikaria on my father for ‘his contribution to the fight against fascism’.

I made a little speech, translated by Topsy, to express profound gratitude to the people of Ikaria for having given my father a Christian burial. Sometimes, during a speech, my throat will contract in a spasm, either when I am emotional or have been nervous beforehand. It happened several times on that hilltop.

We left Ikaria with a brass rocket casing from the Beaufighter and memories as intense as they were difficult to digest.

Now that I know the circumstances of my parents’ marriage and my father’s death, at least in part, and have made my pilgrimage to Ikaria, I have a sense of peace. I have tied some of life’s loose ends.