This Really Exists:

Giant Concrete Arrows That

Point Your Way Across America...

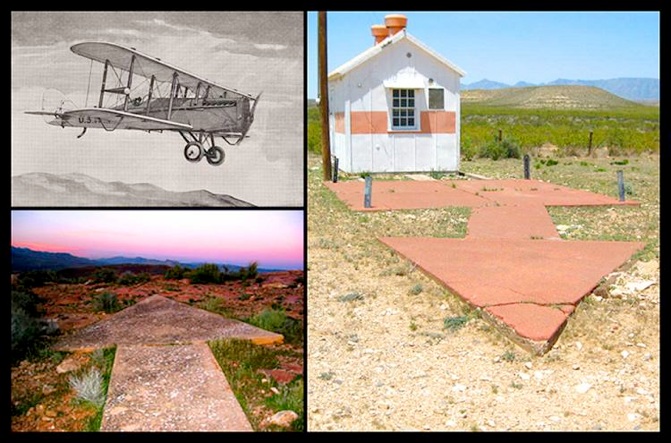

Every so often, usually in the vast deserts of the American Southwest,

a hiker or a backpacker will run across something puzzling:

a large concrete arrow, as much as seventy feet in length,

sitting in the middle of scrub-covered nowhere.

What are these giant arrows? Some kind of surveying mark?

Landing beacons for flying saucers? Earth’s turn signals?

No, it's...

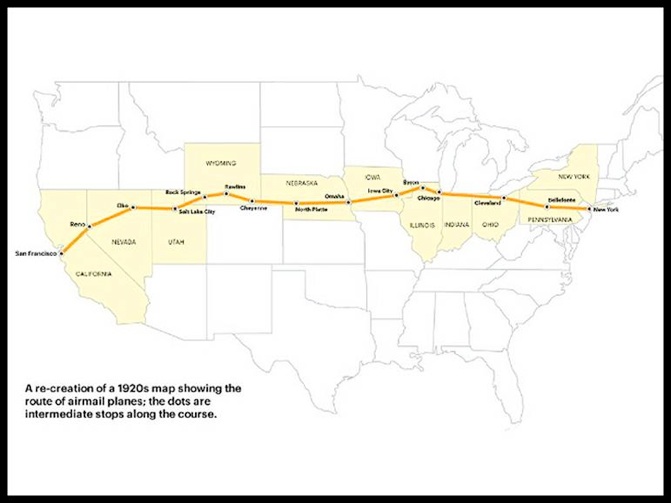

The Transcontinental Air Mail Route.

On August 20, 1920, the United States opened its first coast-to-coast

airmail delivery route, just 60 years after the Pony Express closed up shop.

There were no good aviation charts in those days,

so pilots had to eyeball their way across the country using landmarks.

This meant that flying in bad weather was difficult,

and night flying was just about impossible.

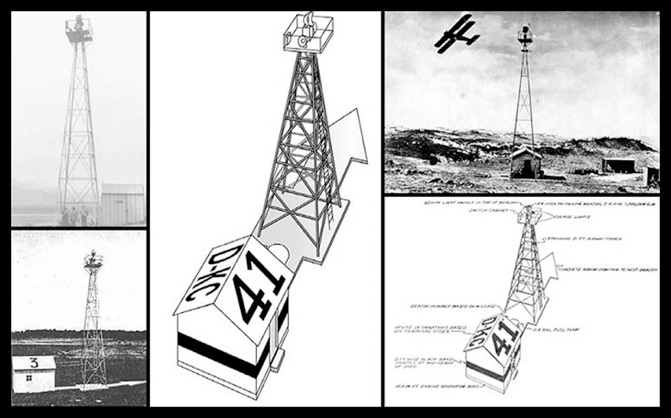

The Postal Service solved the problem with the world’s first ground-based

civilian navigation system: a series of lit beacons that would extend from

New York to San Francisco. Every ten miles, pilots would pass a bright yellow

concrete arrow. Each arrow would be surmounted by a 51-foot steel tower

and lit by a million-candlepower rotating beacon.

(A generator shed at the tail of each arrow powered the beacon.)

Now mail could get from the Atlantic to the Pacific not in a matter of weeks,

but in just 30 hours or so.

Even the dumbest of air mail pilots, it seems, could follow a series of bright

yellow arrows straight out of a Tex Avery cartoon. By 1924, just a year after

Congress funded it, the line of giant concrete markers stretched from Rock Springs,

Wyoming to Cleveland, Ohio. The next summer, it reached all the way to New York,

and by 1929 it spanned the continent uninterrupted, the envy of postal systems worldwide.

Radio and radar are, of course, infinitely less cool than a concrete

Yellow Brick Road from sea to shining sea, but I think we all know how

this story ends. New advances in communication and navigation technology made

the big arrows obsolete, and the Commerce Department decommissioned the beacons

in the 1940s. The steel towers were torn down and went to the war effort.

But the hundreds of arrows remain. Their yellow paint is gone,

their concrete cracks a little more with every winter frost,

and no one crosses their path much, except for coyotes and tumbleweeds.

But they’re still out there.