Dambusters v Elf 'n' Safety: On the 70th anniversary of their legendary raid, jobsworths have banned the war's bravest airmen - and the public - from an official fly-past honouring their courage

-

•70th anniversary of the Dambusters’ Raid will be on Thursday

-

•No official event allowed at Derwent Dam because of traffic it would create

-

•The Squadron smashed the Mohne, Eder and Sorpe dams in 1943

PUBLISHED: 23:01, 12 May 2013 | UPDATED: 02:18, 13 May 2013

Lying face-down in the nose of the lumbering Lancaster bomber, staring through its Perspex nostril, ‘Spam’ Spafford thought his time was up. ‘Christ, this is bloody dangerous!’ the veteran bomb-aimer shouted up at the pilot.

The man at the controls — Wing Commander Guy Gibson — immediately lifted the plane just moments before instant obliteration and pulled away. Gibson and his crew had not been confronted by German fighters or anti-aircraft guns cannon but the dark waters of the same Derbyshire reservoir where I am standing now.

They had just been on their first training run over the Derwent Dam and had immediately discovered the perils of flying a 30-ton bomber at 240mph a few feet above open water in the dark.

Brave: Robert Hardman at the Derwent Dam where the Dambusters had their first training run

Within seven weeks, they would be doing it under enemy fire — in one of the most celebrated, brilliant and tragic episodes in modern warfare: the Dambusters’ Raid. They were the baby-faced volunteers who demolished two vital German assets, wreaked havoc on Hitler’s industrial heartland and gave a battered Britain an almighty shot in the arm. Yet nearly half of those young men would never return.

Today, just three are left on three continents.

Thursday night will be the 70th anniversary of the moment when 24-year-old Guy Gibson led 617 Squadron off into the twilight from Lincolnshire’s RAF Scampton to smash the Mohne, Eder and Sorpe dams with bouncing bombs. The first two fell and the third was damaged.

The resulting tsunami of water and mud would disable or destroy more than 100 factories and power stations, demolish 25 bridges and thousands of buildings and cost Germany huge sums of money and manpower. For Britain and her Allies, it was a source of immense pride. After so many reverses in the early years of the war, things were turning. First, victory in the North African desert. Now this...

Bombs away: Robert Hardman on board a Lancaster Bomber

Among the 400 who will be at Scampton for Thursday’s sunset ceremony will be members of Gibson’s family along with two veterans of the raid, the daughter of the genius behind it all and many, many very proud people still grieving over the events of that night.

Don’t tell Lewis Burpee Jnr that this is just history. He never knew his father, Pilot Officer Lewis Burpee, from Ottawa, whose plane went down in flames. But Lewis has just arrived here from Canada, one of many flying in from all over the world to attend this week’s commemorations.

As well as events at Scampton, there will be various fly-pasts by the RAF’s Battle of Britain Memorial Flight and Friday’s international service at Lincoln Cathedral.

Sadly, the veterans and relatives are unlikely to experience the eternally stirring sight and sound of our last operational Lancaster swooping down over the place where it all began.

On Thursday, it will come thundering down the Derwent Valley and strafe the Derwent Dam — just as Gibson and his men did so many times in those ‘bloody dangerous’ training runs.

The Memorial Flight’s Lancaster will be joined by two Spitfires and two Tornados from today’s 617 Squadron for three spectacular runs right over the target. Earlier on, the devoted locals who run the little dam museum will also be holding their annual memorial service.

But thanks to the health-and-safety brigade, few members of the public will be able to be there, too.

Severn Trent Water, which owns the dam, and other public sector ‘stakeholders’ have decreed heavy traffic on country lanes would pose an unacceptable threat to the emergency services. So there can be no official event at the Derwent Dam.

Veteran: Wing Commander Guy Gibson led his force to the Eder dam

Although the veterans happily drove unscathed to the dam, near Bamford, for the official 65th anniversary event in 2008 (not to mention all the other anniversaries before that), the risk is apparently too great this year.

So access roads to this Peak District beauty spot will be open only to those in walking boots. Everyone else, veterans included, will be directed 20 miles away to Chatsworth, where they can see the fly-past in a pay-and-display car park. No wonder some veterans are rolling their eyes.

‘It’s absolutely ridiculous. Do they think we’re all going to fall into the water?’ asks Mary Stopes-Roe, 85, daughter of inventor Barnes Wallis. He was the softly-spoken colossus who designed the bouncing bomb within a matter of weeks.

One wonders what he would make of today’s ‘stakeholders’, incapable of devising a park-and-ride scheme to ferry a few 617 Squadron families to the dam. But neither Mary nor anyone else is letting this exasperating pusillanimity take the shine off what is a very important anniversary.

Public interest in the commemorations is at a new high, with a live BBC2 programme from RAF Scampton and international media coverage.But more important still is the shift in attitudes. For we finally seem to be overturning the fashionable post-war argument — drummed into a generation of schoolchildren — that the raid was little more than a propaganda exercise which inspired a great film.

It has taken 70 years — just as it took nearly 70 years to erect a national memorial to the men of Bomber Command — but the scale of the achievement is finally being acknowledged. So what is the true story?

By 1943, as the crews of Bomber Command suffered terrible losses in their efforts to pulverise Germany’s industry and infrastructure, Barnes Wallis, an outstanding Vickers engineer, came up with a plan. Take out certain enemy dams, he argued, and the collateral damage would be more devastating than countless ordinary raids.

Yet, the waters in each dam contained steel nets preventing the logical means of attack — by torpedo. Watching his daughter flicking marbles across a tub of water, Wallis had a brainwave.

Why not build a spinning bomb which could also bounce across the water and explode with enough force to crack the wall? The weight of the water would do the rest. His idea was rubbished at first, but he finally won over the top brass in late February 1943.

But the dams would have to be attacked before the end of May or the water levels would be too low to force a collapse. And it would require an exceptional group of men. The race was on.

Guy Gibson, the son of a colonial officer in India, had shone in the RAF as both a fighter and bomber pilot. He was not universally liked — some found him unnecessarily superior and foul-tempered — but all great leaders have their flaws.

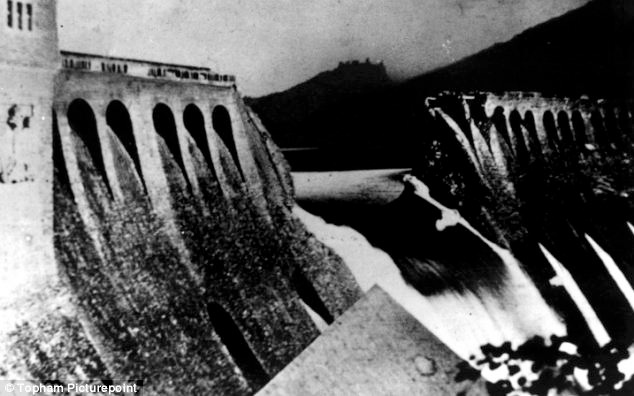

Piece of history: The Derwent Dam, where the trial flights took place in the Peak District

And he was, unquestionably, a superb one. Having created a new squadron from scratch, he had just a few weeks to train them how to use a new secret weapon in near-suicidal conditions. Then he led 19 aeroplanes half way across Europe at tree height — to avoid enemy radar.

They would have to attack one by one, and each plane had just one bouncing bomb. At the Mohne dam, they met a wall of anti-aircraft fire and Gibson went in first.

His bomb failed to do the trick, but he then accompanied plane after plane on its run through the hail of shells, drawing enemy fire. It was after the fourth attempt, by Squadron Leader ‘Dinghy’ Young DFC, that the Mohne finally cracked with such devastation that Germans still call it the ‘Mohnekatastrophe’.

Gibson led part of his surviving force on to the Eder dam, which they finally smashed with their very last bomb. Just ten miles away at the Sorpe dam, two more crews also landed their bombs on target, although the badly-damaged wall stood firm.

Of the 19 planes which had set out, eight were shot down or hit power lines and exploded. Three more limped home without ever reaching the target. Of 133 men, 53 were killed and three crash survivors were taken prisoner.

The cost had been terrible. But hundreds of millions of cubic metres of water, mud and rubble which crashed through Germany’s industrial heartland would cause more damage to military production and morale than months of bombing raids — with all the casualties those would have involved.

No ceremony: Despite the significance of the anniversary there can be no official event at the Derwent Dam because of the heavy traffic it would create

After the raid, Gibson and his men were rightly feted as national heroes with 33 decorations, including the Victoria Cross for Gibson himself.

The fact so many, including Gibson, would not survive the war only reinforced a mythology compounded by the classic 1955 film, The Dam Busters. Thereafter, few would ever refer to the mission by its official name, Operation Chastise.

But then came the inevitable pendulum of historical revisionism, pooh-poohing the big-screen depiction of it. Come the Sixties, the consensus was that the Dambusters, though very brave, had achieved little more than a propaganda coup. The principal evidence for this argument was indisputable.

Within five months, Germany had rebuilt the Mohne and Eder dams. According to German records, most industrial production had recovered by then, too. Thus, it was argued, the raid had barely scratched the Nazi war effort.

But then that is exactly what the Nazi spin machine wanted everyone to think at the time.

Now a new generation of historians has looked afresh at the question: was it a success? The answer: it was a stupendous achievement.

‘On every count, it was an amazing result,’ says the historian James Holland, who has just published a new edition of his powerful bestseller, Dam Busters: The Race To Smash The Dams.

‘The fact the Germans had to rebuild the dams so quickly is proof of how important they were. They diverted vital resources away from other fronts — just to build the new railway lines and barracks and defences before they could even start building the dams. And it cost them £5.6 billion in today’s money, quite apart from the manpower.’

Success: The Eder Dam bursting after the raid of 1943

The damage went far beyond the destructive power of the floods. With no water, entire industries seized up. When the RAF stepped up summer raids in the area, the German fire brigades had no water. Supplies to the front were drying up and, suddenly, Germany was being defeated — from Russia to Sicily.

The Mohne dam, in particular, was a German national symbol, much like Big Ben in Britain. Built in 1913, it was seen as a shining example of their ability to tame nature. Thus, Hitler’s chief architect, Albert Speer, decreed rebuilding work should take priority over everything else.

As a result, fortification work along France’s ‘Atlantic Wall’ was downgraded while supplies and workers were diverted to the Ruhr. How many extra gun batteries would have stood along the Normandy coast to slaughter the Allied forces when they landed a year later?

Next year is the 70th anniversary of D-Day. Ask those Normandy veterans if they think the Dambusters’ raid was a waste of time.

Speaking from his Bristol care home, George ‘Johnny’ Johnson DFM, Britain’s last surviving veteran of the raid, is still enraged by those historians who talk it down.

War effort: One of the Dambusters squadron dropping a bomb in 1943

‘If I ever meet one of them, I hope I have both hands tied behind my back,’ says the 91-year-old bomb-aimer who patiently ordered one agonising run after another over the Sorpe in order to plant his bomb on target. ‘And don’t forget it showed Hitler that what he thought was impregnable could be destroyed.’

James Holland hopes fresh interest in the raid may also curtail the tedious row about a minor footnote to the raid — Gibson’s black Labrador (killed by a car just hours before the raid).

As anyone who has seen the film will know, it was called ‘Nigger’. The same word was the victorious code to let HQ know the Mohne had cracked. The same word is still on the marble slab above the dog’s well-tended grave which lies outside Number Two hangar at Scampton.

However awkward it may be, it is a historical fact. Yes, the word is now deeply offensive but, no doubt, many of Gibson’s vintage would be deeply offended by people walking today’s streets in French Connection T-shirts saying ‘FCUK’.

‘When I was writing my book, nine out of ten people would say: “What are you going to call the dog?” ’ sighs Holland, who will be discussing the raid at next month’s Chalke Valley History Festival. ‘People know about Barnes Wallis, Gibson and the dog — but what about all the others?’

Majestic: A Lancaster Bomber as used to demolish two vital German dams

A painting depicts the daring bombing raids by the the 617 Squadron of the RAF during the Second World War

Now more people are finding out about all the others — among them Lewis Burpee and ‘Dinghy’ Young, shot down and killed with all his crew just as they were crossing the Dutch coast for home.

Crowds are flocking to 617’s old headquarters, newly-restored at RAF Scampton; to the Memorial Flight’s home at RAF Coningsby; to the old officers’ mess at the Petwood Hotel in Woodford Spa.

More and more people are turning up at Vic Hallam’s delightful museum in the western tower of the Derwent Dam where he has also erected a memorial to the Dambusters. Despite Thursday’s road closures, Vic is determined to stage his annual memorial service with as much dignity as he can. He has even paid for a mobile loo for any veterans who actually make it.

At RAF Coningsby, I am lucky enough to look inside the Lancaster as it prepares for this week’s great events. It is profoundly moving just to sit in the cockpit of the old beast, to feel the weight of the joystick, to smell the oil, to squeeze in to the bomb-aimer’s cramped eyrie, to crawl back into the rear-gunner’s turret. Bashing my head and limbs, I realise what a lonely, claustrophobic tomb this must have been for so many ‘Tail end Charlies’.

Such was life for all the bomber boys. So let us remember them all in the days ahead. At the same time, let us look afresh at that breathtaking display of daring, ingenuity and self-sacrifice that not only had a huge effect on the wartime generation. It inspires us still.